How low is too low?

When should you be concerned about being too low in glucose?

How Low Is Too Low for Your Glucose Level When Exercising, Competing, or in Life?

Maintaining stable blood glucose levels is critical for overall health, particularly during physical activity, competitive sports, or even daily life. Hypoglycemia, or low blood glucose, will definitely impair physical performance, cognitive function, and, in severe cases, lead to life-threatening complications. This article explores what constitutes dangerously low glucose levels, how they affect the body during exercise or competition, and practical strategies to prevent and manage hypoglycemia. With insights grounded in medical understanding, we’ll provide key tips to help you stay safe and perform at your best.

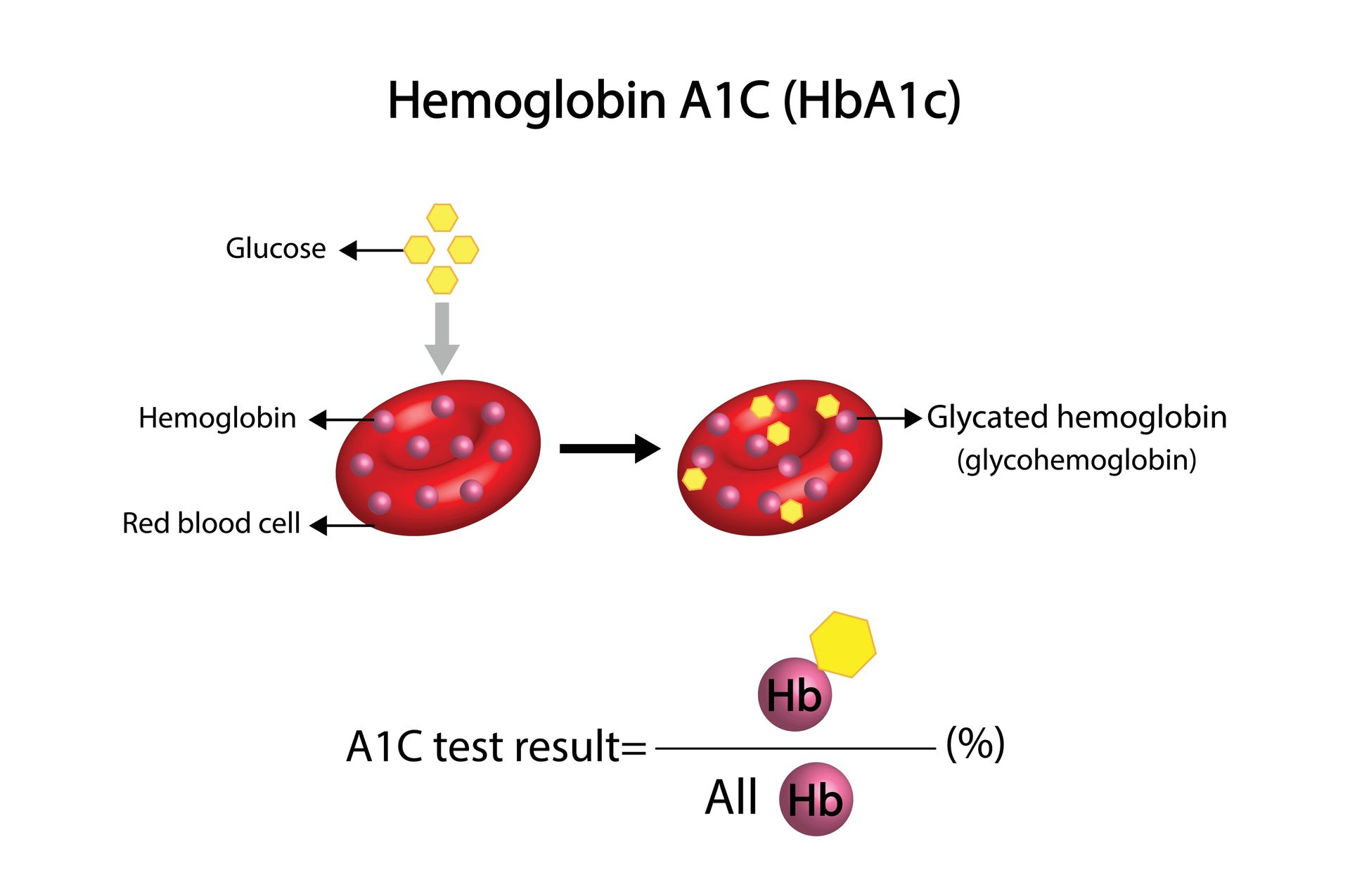

Understanding Blood Glucose and Hypoglycemia

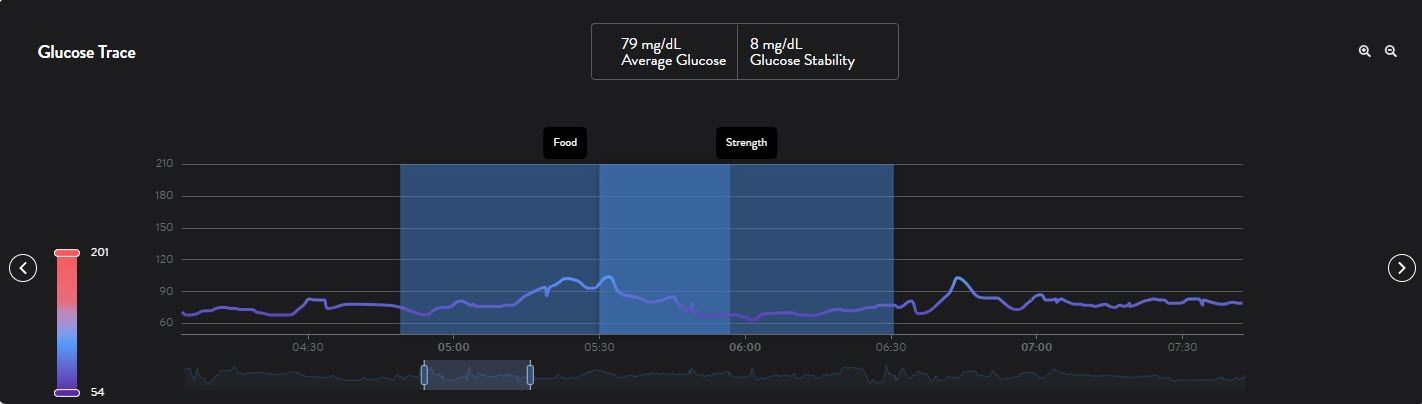

Blood glucose, measured in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or millimoles per liter (mmol/L), is the primary energy source for your muscles, brain, and other organs. Normal fasting (before breakfast in the morning) blood glucose levels typically range from 70–99 mg/dL (3.9–5.5 mmol/L). Hypoglycemia is generally defined as a blood glucose level below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), though symptoms and risks vary by individual, activity level, and health status. Please note that everyone is different, and women tend to be lower than men, so women might see their glucose in the 60-70mg/dL range.

During exercise or competition, your muscles demand more glucose, which can deplete blood sugar rapidly, especially for people with diabetes or those engaging in prolonged or intense activities. In daily life, factors like fasting, stress, or medication can also lower glucose levels.

Knowing how low is "too low" depends on recognizing the thresholds where symptoms and risks emerge.

How Low Is Too Low?

Medical guidelines categorize hypoglycemia into three levels based on blood glucose readings and symptoms:

- Level 1 (Mild Hypoglycemia): Blood glucose between 54–70 mg/dL (3.0–3.9 mmol/L). Symptoms may include shakiness, sweating, or mild confusion, but individuals can often self-treat.

- Level 2 (Moderate Hypoglycemia): Blood glucose below 54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L). Symptoms intensify, including difficulty concentrating, irritability, or coordination issues, often requiring assistance.

- Level 3 (Severe Hypoglycemia): Blood glucose so low it causes unconsciousness, seizures, or inability to self-treat, typically below 40 mg/dL (2.2 mmol/L), though exact thresholds vary.

For athletes or those exercising, even mild hypoglycemia will impair performance, while moderate to severe levels pose serious risks. In daily life, prolonged or severe hypoglycemia can lead to neurological damage or coma if untreated.

Why Glucose Levels Drop During Exercise or Competition

Exercise increases glucose uptake by muscles, especially during aerobic activities like running or cycling, which rely heavily on blood sugar and glycogen stores. Several factors contribute to hypoglycemia risk:

- Intensity and Duration: High-intensity or prolonged exercise (over 60–90 minutes) depletes glucose faster.

- Insulin Resistance or Sensitivity: In people who have insulin resistance, glucose may stay up longer but then drop rapidly and somewhat unexpectedly. For those with diabetes, insulin doses or timing may not align with exercise demands, causing glucose to drop. For those with excellent insulin sensitivity, you may quickly pull the glucose out of your bloodstream and into your muscles in such a way that it drops your glucose level. In combination with working out simultaneously, you might just have the "double whammy" effect because you are so insulin sensitive.

- Carbohydrate Intake: Inadequate fueling before or during activity can lead to low glucose.

- Dehydration or Heat: These can exacerbate glucose fluctuations.

- Stress and Adrenaline: Competitive settings may spike adrenaline, initially raising glucose but leading to a crash later.

In daily life, skipping meals, excessive alcohol, or medications like insulin or sulfonylureas can also trigger hypoglycemia, particularly in those with diabetes.

Symptoms of Low Blood Glucose (Bonking)

Recognizing hypoglycemia early is crucial. Symptoms vary but often include:

- Physical: Trembling, sweating, weakness, hunger, or palpitations.

- Cognitive: Confusion, difficulty focusing, irritability, or anxiety.

- Neurological: Dizziness, blurred vision, or, in severe cases, seizures or unconsciousness.

During exercise, symptoms like fatigue or shakiness may be mistaken for normal exertion, making monitoring essential, especially for athletes with diabetes.

Risks of Low Glucose During Exercise or Competition

Hypoglycemia during physical activity can lead to:

- Reduced Performance: Impaired muscle function and coordination.

- Injury: Dizziness or confusion increases the risk of falls or accidents.

- Cognitive Impairment: Poor decision-making in competitive settings.

- Severe Outcomes: Seizures, loss of consciousness, or long-term neurological damage if untreated.

In daily life, untreated hypoglycemia can disrupt work, driving, or other tasks, with severe cases requiring emergency intervention.

Key Tips for Preventing and Managing Low Glucose

To maintain safe glucose levels during exercise, competition, or daily life, follow these evidence-based strategies:

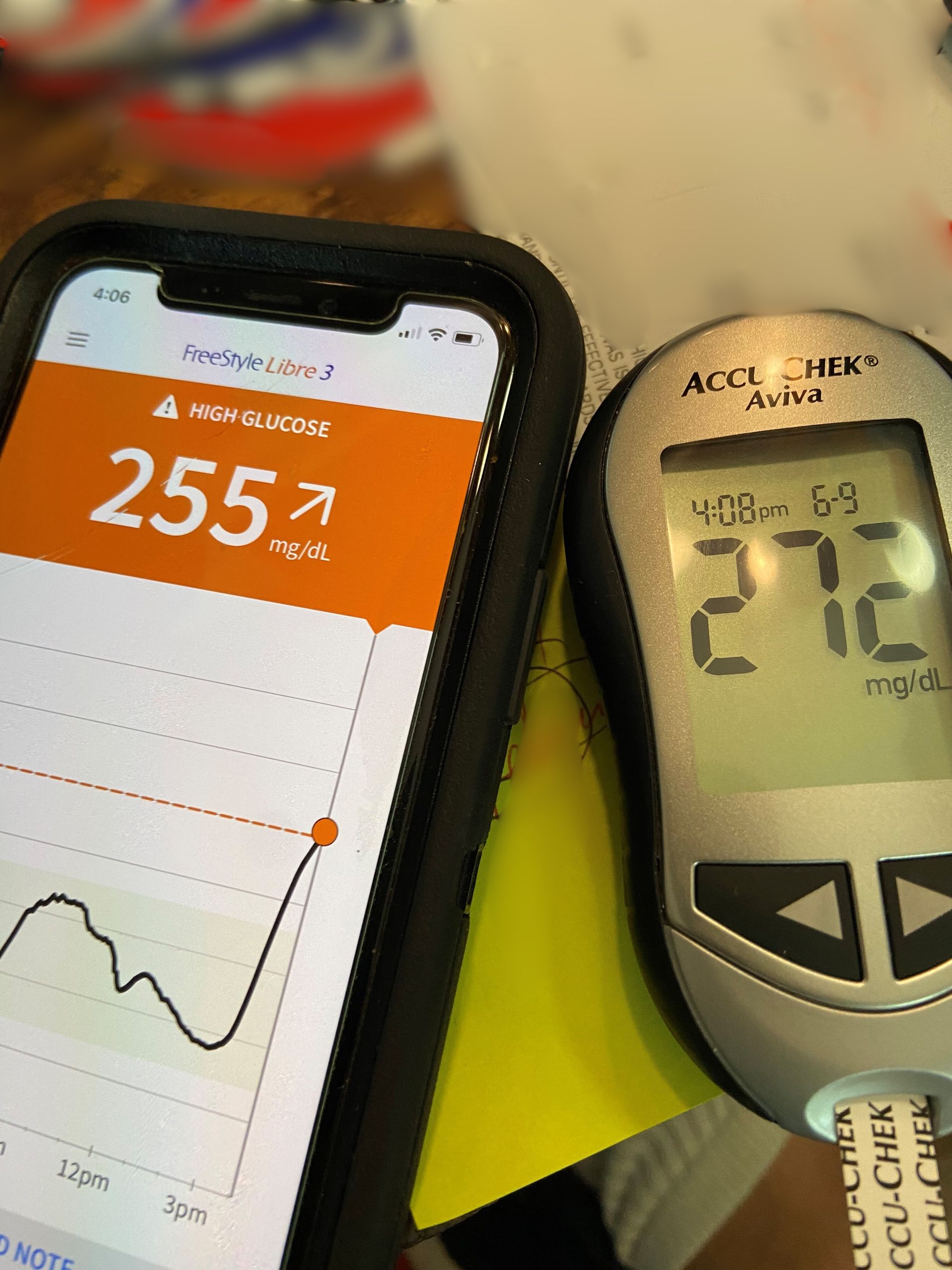

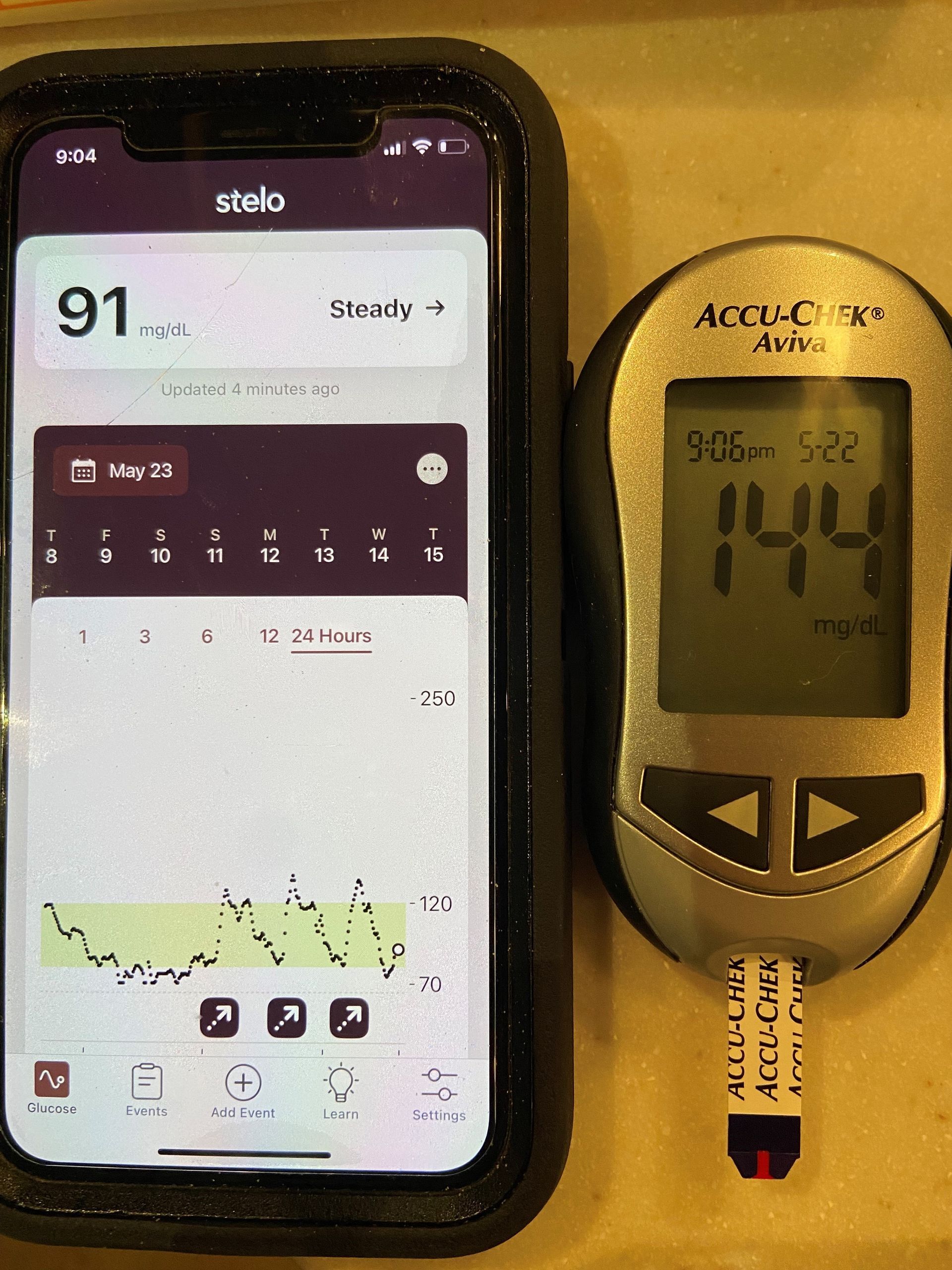

- Monitor Blood Glucose Regularly

- Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) or glucometer before, during, and after exercise.

- Check levels every 30–60 minutes during prolonged activity or if symptoms arise.

- In daily life, test if you feel off or after potential triggers like fasting or medication.

- Fuel Properly Before (Priming) and During Activity

- Consume 15–30 grams of carbohydrates 10-15 MINUTES before exercise (e.g., a banana, toast, or energy gel).

- For sessions lasting over an hour, take 60-90 grams of carbs every 30–60 minutes (e.g., sports drinks, gels, or dried fruit).

- In daily life, avoid skipping meals and include balanced carbs, proteins, and fats to stabilize glucose.

- Adjust Medications with Medical Guidance

- For people with diabetes, consult your doctor to adjust insulin or oral medications before exercise or competition.

- Reduce insulin doses by 20–50% for planned activity, depending on intensity and duration.

- Be cautious with evening exercise, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur during sleep.

- Know Your Body’s Response

- Track how different activities, foods, or stressors affect your glucose levels.

- Be aware that high-intensity exercise may initially raise glucose due to adrenaline, followed by a drop hours later.

- In daily life, note patterns (e.g., morning lows or post-meal crashes) to anticipate risks.

- Carry Fast-Acting Carbohydrates

- Always have 15–30 grams of fast-acting carbs on hand, such as gels, chews or sports drink.

- During exercise, keep these accessible (e.g., in a pocket or with a coach).

- In daily life, carry them in your bag or car, especially if you’re prone to lows.

- Treat Hypoglycemia Promptly (The 15-15 Rule)

- If glucose is below 70 mg/dL or symptoms appear, consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbs (e.g., 4 oz juice or 1-2 sports gels).

- Wait 15 minutes, then recheck glucose. Repeat if still below 70 mg/dL.

- Once stable, eat a snack with carbs and protein (e.g., a peanut butter sandwich) to prevent recurrence.

- Stay Hydrated and Manage Stress

- Drink water or electrolyte-rich fluids during exercise to support glucose regulation.

- In competition, practice stress management techniques like deep breathing to minimize adrenaline spikes.

- In daily life, moderate alcohol and manage stress to avoid glucose fluctuations.

- Plan for Post-Exercise Recovery

- After exercise, make a recovery shake with a 2:1 up to a 4:1 Carb to protein ration to create a glucose spike, which in turn causes the pancreas to release insulin and then help absorb those carbs and proteins into your cells more quickly and completely.

- After exercise, eat a balanced meal or snack within 1–2 hours to replenish glycogen stores.

- Monitor glucose overnight, as delayed hypoglycemia is common 6–12 hours post-exercise.

When to Seek Emergency Help

If blood glucose doesn’t rise after two 15-gram carb treatments, or if symptoms worsen (e.g., confusion, seizures, or unconsciousness), seek emergency help immediately. Call 911 or administer glucagon (if prescribed) for severe hypoglycemia. During exercise or competition, stop activity and prioritize treatment.

Special Considerations

- People with Diabetes: Face higher hypoglycemia risks due to insulin or medication use. CGMs and careful planning are critical.

- Non-Diabetic Athletes: May experience exercise-induced hypoglycemia (reactive hypoglycemia) if under-fueled or overexerted.

- Children and Elderly: Are more vulnerable to severe hypoglycemia and may need closer monitoring.

- Daily Life Triggers: Stress, illness, or hormonal changes can lower glucose unexpectedly, even without exercise.

Conclusion

Understanding how low is "too low" for your glucose levels is essential for safe exercise, competition, and daily living. Blood glucose below 70 mg/dL signals mild hypoglycemia, while levels below 54 mg/dL or severe symptoms demand urgent action. You can prevent and manage low glucose by monitoring regularly, fueling appropriately, and following the key tips outlined. Whether you’re an athlete, a person with diabetes, or simply navigating life’s demands, proactive glucose management empowers you to stay healthy, safe, and at your best.