Are glucose spikes bad?

Should I be worried about a glucose spike?

Are Glucose Spikes Bad for Athletes? Impact on Athletic Performance

For athletes, blood glucose levels are a critical factor in optimizing performance, recovery, and endurance. Glucose, the body’s primary energy source, fuels muscles and the brain during exercise. However, glucose spikes—rapid increases in blood sugar followed by sharp drops—can disrupt energy availability, focus, and recovery. This article examines whether glucose spikes are detrimental for athletes, how they affect athletic performance, and practical strategies to manage them during training and competition. Tailored specifically for athletes, we’ll explore the science behind glucose dynamics and provide actionable tips to maintain stable energy levels for peak performance.

Understanding Glucose Spikes in Athletes

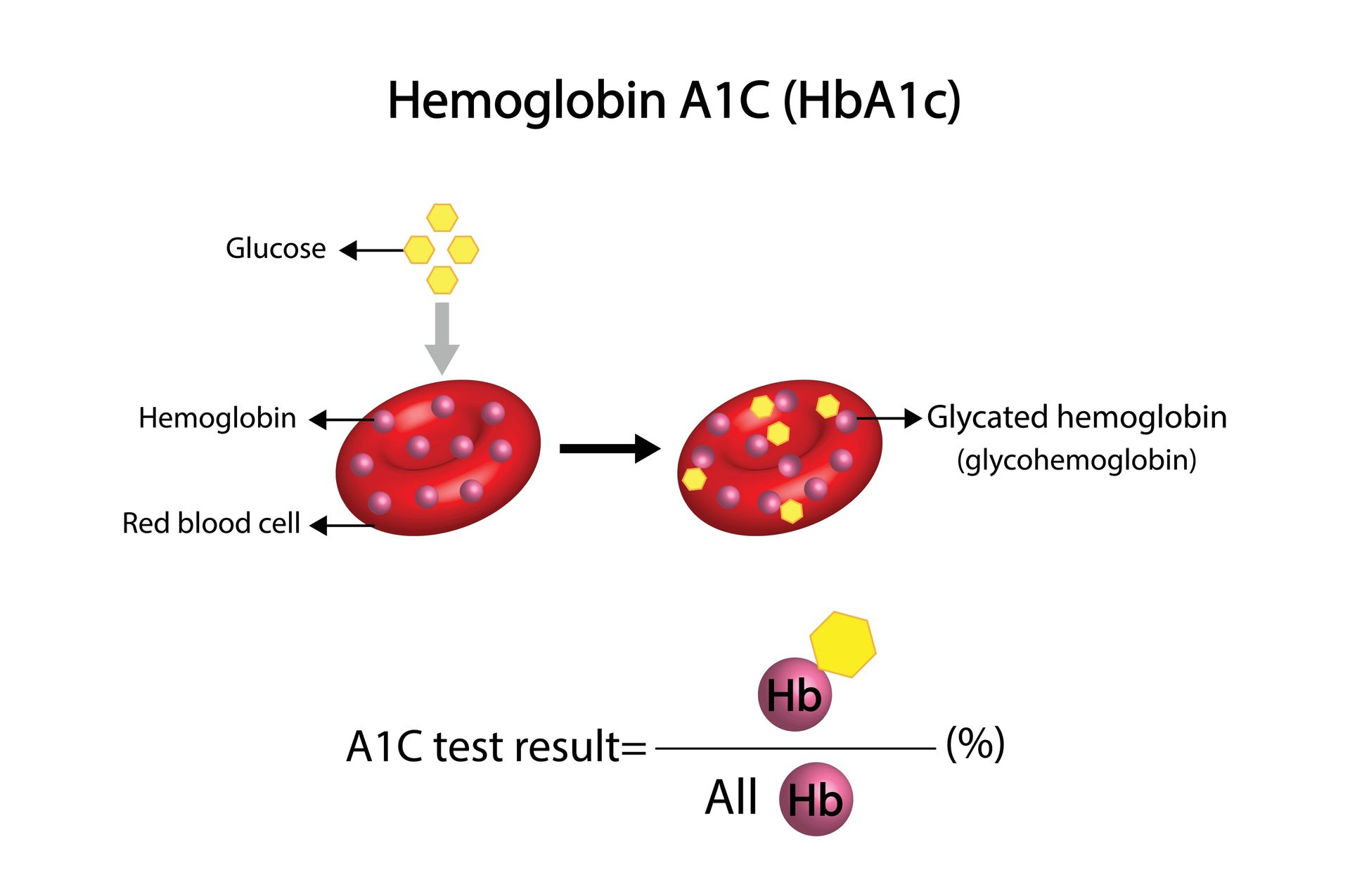

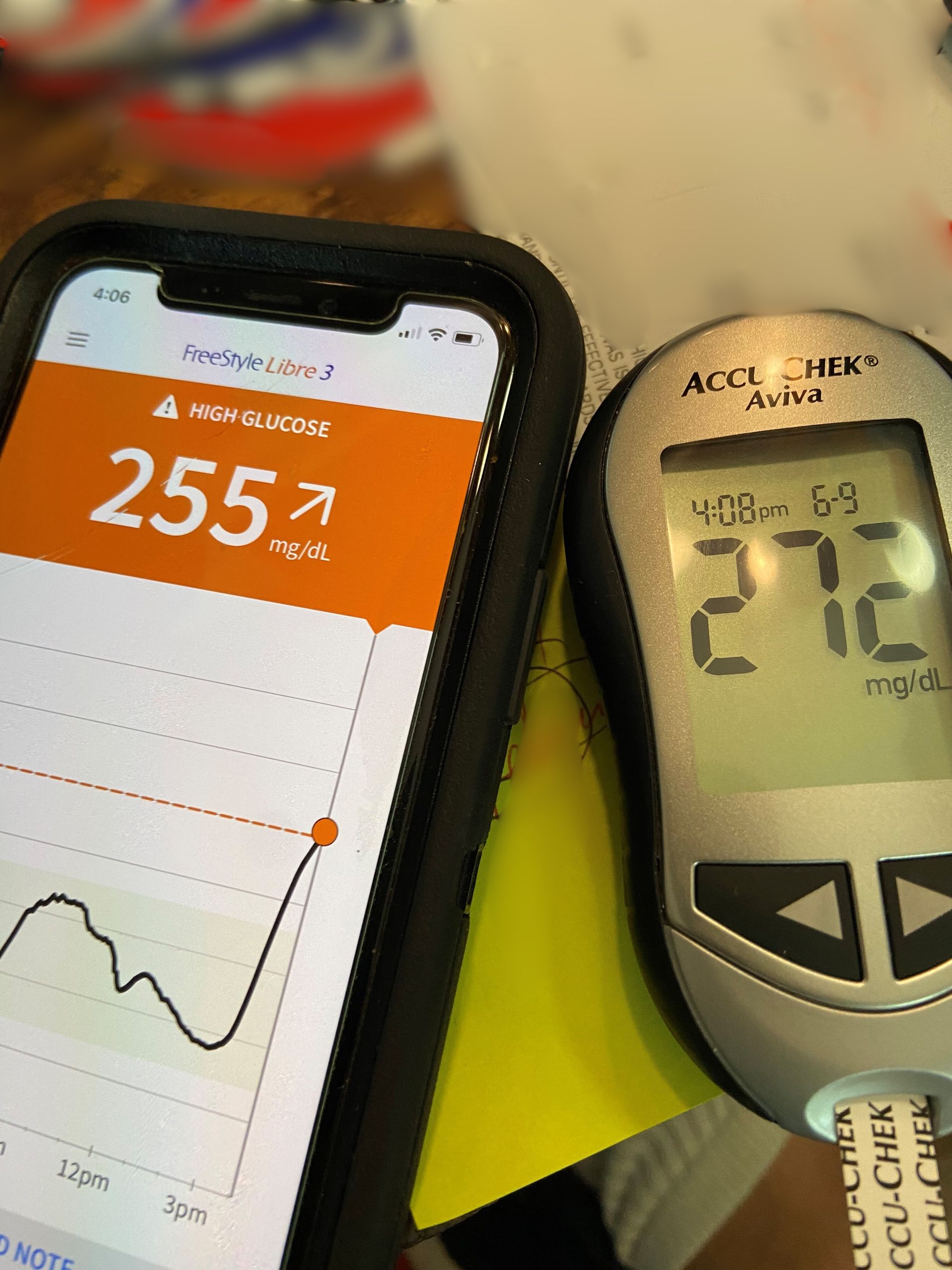

A glucose spike occurs when blood glucose levels rise sharply, often above 140–180 mg/dL (7.8–10 mmol/L) within 1–2 hours after eating, followed by a rapid drop. In athletes, spikes can be triggered by high-carbohydrate meals, energy gels, sports drinks, or stress hormones like adrenaline during competition. While glucose is essential for fueling exercise, excessive or poorly timed spikes can lead to performance issues, particularly during high-intensity or endurance activities.

For athletes, the concern isn’t just the spike itself but the subsequent crash (reactive hypoglycemic crash- Read more about this in my book), which can cause fatigue, reduced coordination, and mental fog. Stable glucose levels—ideally maintained between 70–140 mg/dL (3.9–7.8 mmol/L) during exercise—support consistent energy delivery and cognitive function.

Are Glucose Spikes Bad for Athletic Performance?

Glucose spikes aren’t inherently harmful in the short term, as athletes often rely on quick-digesting carbs to fuel performance. However, frequent or poorly managed spikes can negatively impact training and competition in several ways:

- Crashes: A spike followed by a drop (below 70 mg/dL) can lead to hypoglycemia, causing weakness, shakiness, and reduced power output. Many athletes do not realize that THEY are creating these.

- Impaired Focus: Rapid glucose fluctuations affect the brain, leading to poor decision-making or loss of focus in critical moments (e.g., during a race or match).

- Fatigue and Recovery Issues: Repeated spikes may stress insulin response, leading to glycogen depletion and slower muscle recovery.

- Gastrointestinal Distress: High-carb intake causing spikes can lead to bloating or nausea, especially during endurance events.

- Long-Term Health: For athletes with or without diabetes, chronic spikes may increase inflammation or insulin resistance, though this is less immediate for performance. Although this is up for debate and what is higher for athletes, might not be a factor as we are constantly turning the glucose over, versus a sedentary person.

Conversely, controlled glucose rises (e.g., from a pre-workout snack) are beneficial, providing readily available energy. The key is timing, quantity, and type of carbohydrate to avoid excessive spikes and crashes.

Factors Influencing Glucose Spikes in Athletes

Several factors contribute to glucose spikes during athletic activities:

- Carbohydrate Type and Timing: High-glycemic foods (e.g., white bread, sugary gels) cause faster spikes than low-glycemic options (e.g., UCAN Sports Nutrition, Almond butter with Eziekel bread).

- Exercise Intensity: High-intensity exercise (e.g., sprints) may initially raise glucose due to adrenaline, followed by a drop, while moderate aerobic exercise lowers glucose steadily.

- Adrenaline and Stress: Competitive settings or pre-event nerves can spike glucose via stress hormones, even without food intake.

- Hydration and Fatigue: Dehydration or glycogen depletion can exacerbate glucose fluctuations.

- Individual Differences: Athletes with diabetes or varying insulin sensitivity respond differently to carbs and exercise.

Impact on Different Types of Athletes

- Endurance Athletes (e.g., Marathoners, Cyclists): Need sustained glucose availability over hours. Spikes from over-fueling can lead to crashes, reducing stamina.

- Power Athletes (e.g., Weightlifters, Sprinters): Rely on short bursts of energy. Spikes may be less disruptive but can impair focus or recovery if poorly timed.

- Team Sport Athletes (e.g., Soccer, Basketball): Require consistent energy and mental clarity. Spikes can disrupt performance during prolonged or intermittent high-intensity efforts.

Key Considerations for Managing Glucose Spikes

Athletes can minimize the negative effects of glucose spikes by adopting strategies tailored to their sport, body, and training demands. Below are critical considerations and practical tips to optimize glucose stability and athletic performance.

- Choose Low- to Moderate-Glycemic Carbohydrates

- Opt for complex carbs like UCAN Sports Nutrition products. This is what I use. Here's a discount for you. Choose whole grains, fruits, or legumes 2–3 hours before exercise to provide steady energy without sharp spikes.

- During exercise, use moderate-glycemic sources like bananas or sports drinks with maltodextrin for sustained release, rather than pure glucose gels.

- Example: A pre-workout meal of oatmeal with berries is less likely to cause a spike than a sugary energy bar.

- Time Your Carbohydrate Intake

- Consume 30–60 grams of carbs 1–2 hours before exercise to top off glycogen stores without overloading blood glucose.

- For sessions over 60–90 minutes, take 30-40 grams of carbs every 30–45 minutes to maintain levels without spiking.

- Post-exercise, pair carbs with protein (e.g., a smoothie with fruit and whey) within 30–60 minutes to replenish glycogen without excessive spikes.

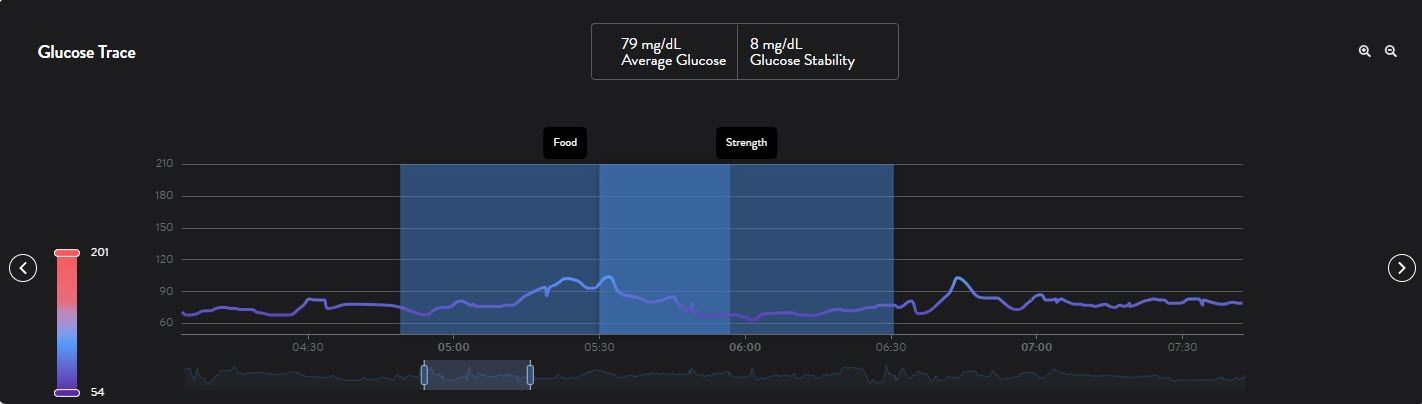

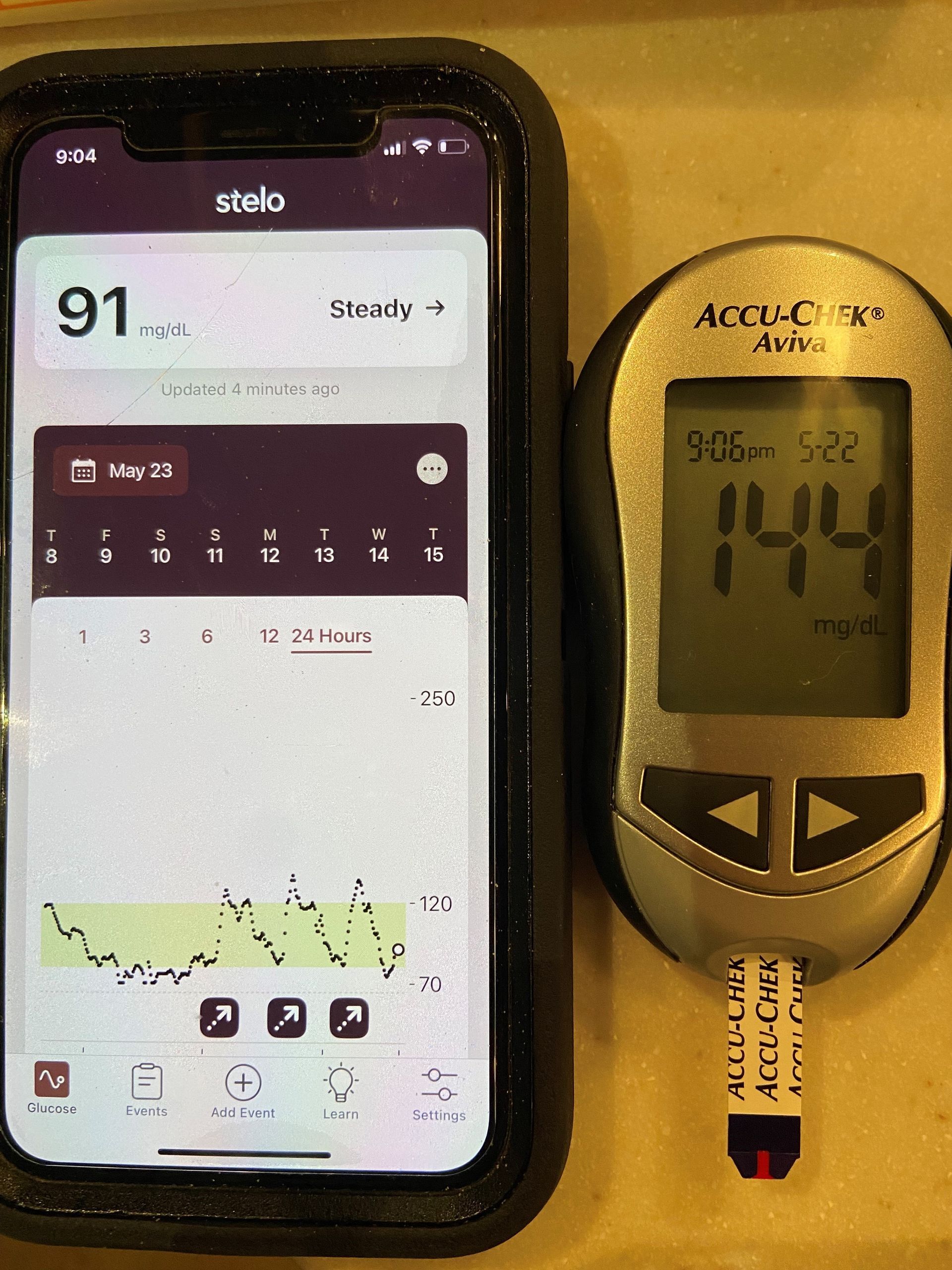

- Monitor Glucose Levels with a CGM

- Use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) during training to track real-time glucose trends, especially for athletes with diabetes or those prone to crashes.

- Check glucose before, during (if feasible), and after exercise to identify patterns and adjust fueling.

- Non-diabetic athletes can benefit from CGMs to fine-tune nutrition strategies.

- Balance Macronutrients

- Pair carbs with protein or healthy fats in pre-workout meals to slow digestion and reduce spike severity (e.g., toast with avocado and egg).

- Avoid consuming carbs alone during long sessions; include small amounts of protein or fat (e.g., a nut butter packet) to stabilize glucose.

- Adjust for Exercise Intensity and Duration

- For high-intensity, short-duration workouts (<45 minutes), minimal carbs may be needed unless glycogen is depleted.

- For endurance events, plan carb intake to match energy expenditure (e.g., 60–90 grams/hour for ultra-marathons).

- Be cautious with adrenaline-driven sports; monitor for delayed crashes after competition.

- Stay Hydrated

- Dehydration impairs glucose regulation. Drink water or electrolyte-rich fluids (4–8 oz every 15–20 minutes during exercise).

- Avoid sugary sports drinks unless carbs are needed, as they can cause unnecessary spikes.

- Test and Personalize Fueling Plans

- Experiment during training (not competition) to find carb types, amounts, and timing that minimize spikes for your body.

- Keep a log of glucose responses, performance, and symptoms to refine your strategy.

- Work with a sports dietitian to tailor plans, especially for athletes with diabetes or unique metabolic needs.

- Manage Competition Stress

- Practice relaxation techniques (e.g., deep breathing, visualization) to reduce adrenaline-driven glucose spikes before events.

- Stick to familiar pre-competition meals to avoid unexpected glucose fluctuations.

- Recover Strategically

- After exercise, prioritize glycogen replenishment with a carb-protein recovery shake. Use a 2:1 -4:1 Carb: protein ratio for maximum absorption. And then eat a good, healthy plant-forward meal to stabilize glucose and support muscle repair in the next hour or two.

- Monitor for delayed hypoglycemia (6–12 hours post-exercise), especially after intense or prolonged sessions, and have a snack if needed.

When Are Glucose Spikes Acceptable?

Small, medium, and even high controlled glucose rises are normal and beneficial during exercise, especially for endurance athletes needing quick energy. For example, a sports gel raising glucose to 120-180 mg/dL during a marathon can sustain performance without harm. The goal is to avoid extreme spikes (e.g., >180 mg/dL) or crashes (<70 mg/dL) that disrupt energy or focus.

Special Considerations for Athletes

- Athletes with Diabetes: Must balance insulin, carbs, and exercise to prevent spikes and lows. CGMs and medical guidance are essential.

- Non-Diabetic Athletes: May experience reactive hypoglycemia from over-fueling. Focus on balanced, timed nutrition.

- Young or Novice Athletes: May be less aware of glucose symptoms. Education and monitoring are key.

- Elite Athletes: Small glucose fluctuations can mean the difference between winning and losing. Precision fueling is critical.

Conclusion

Glucose spikes are not inherently bad for athletes but can harm performance if they lead to crashes, fatigue, or mental fog. By choosing the right carbs, timing intake, monitoring glucose, and personalizing strategies, athletes can maintain stable energy levels for optimal training and competition. Whether you’re a sprinter, marathoner, or team sport athlete, managing glucose effectively enhances endurance, focus, and recovery. Test your approach, stay consistent, and consult professionals to fine-tune your plan for peak athletic performance.